On this page

- Support for authors

- Requirements

- How to make a good kata?

- Kata Idea and Duplicates

- Kata quality

- Learning from experience

- Setting up the kata

- Kata Properties

- Name

- Discipline

- Estimated rank

- Tags

- Allow Contributors?

- Description

- Code Snippets

- Complete Solution

- Initial Solution

- Preloaded

- Test Cases

- Example Test Cases

- Before publishing

- Train on your kata

- Verify quality guidelines

- Ask for a review of your draft

- After publishing

Creating your first kata

On Codewars, kata are created by regular users, who decided to share their idea with the community and create a task others could train on. People can come up with great ideas, and well-crafted kata are a source of great fun for everyone. After solving some kata, everyone sooner or later wants to contribute and create something others would enjoy to work on. Additionally, creating a kata can be a great learning experience.

However, authors sometimes do not realize the fact that creating a good quality kata is much harder than solving it. Creating kata is a totally different kind of task from solving kata. It requires a much wider mindset and set of skills. Creating a kata is much closer to "professional" tasks: it requires you to design a task with a large set of target users in mind, write a solution, create tests for it, handle feedback from users, and maintain it by fixing bugs. Every kata is a small software product in itself, and goes through a small equivalent of a full software development lifecycle!

Support for authors

To support you with this difficult task, a set of help pages has been created with the following types of information:

- Tutorials, for users who are still figuring things out.

- Guidelines, which need to be respected to meet the Codewars quality criteria. It is strongly recommended to become familiar with these, otherwise you risk that your kata will be met with bad reception, harsh remarks, and many reported issues.

- HOWTOs explaining how to realize some commonly occurring tasks, or solve commonly repeating problems.

- Language specific pages with code snippets, examples, references, and tutorials related to specific programming languages.

You can also reach out directly to the community to ask questions and seek experienced users' advice on the kata-authoring-help Gitter channel.

Requirements

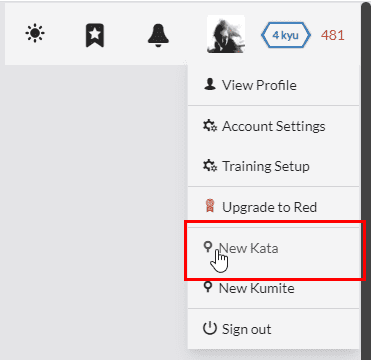

To create a new kata, you need to earn the "Create Kata" privilege. After reaching the required amount of 300 Honor points, the privilege is granted and you can select the "New Kata" option from the profile menu:

How to make a good kata?

Everyone enjoys good, wellcrafted kata, and no one likes to struggle with poorly authored challenges. However, especially for unexperienced authors, it's often difficult to tell what is good, what is bad, or why. There's a few aspects which can drastically influence experience of other users with your kata and, as a result, feedback it will receive.

Kata Idea and Duplicates

At the time of writing, there are already over 6500 approved kata, and almost 2500 beta kata. It's a vast red ocean out there - if you're still sticking to ideas like Fizzbuzz, Fibonacci numbers, or Caesar/ROT cipher, it's pretty much 99.999999...% chance that someone has done this before you.

This is bad because creating a kata about them again constitutes a duplicate kata, and we certainly don't want 100 Fizzbuzz kata out in the wild. When a duplicate is found it will be retired, which basically means it gets taken out of the kata catalog.

To make sure users will like the idea presented in your kata, you can:

-

Try to come up with some novel and original idea. It would mean not only creating some original theme or backstory, but the task should also ideally boil down to some new, interesting approach. There's already many kata which can be brought down to one of very popular ideas:

- Topics common when learnign programming. Fibonacci, fizz-buzz, factorial, there's already plenty of them.

- Simple map/filter/reduce operations on a list or array. There's too many kata which require just to iterate over a sequence and pick/reject/transform some of its elements based on some simple criteria.

- Calculating a result of a formula, be it mathematical, physical, or chemical. Substituting values into a formula has been done many times.

- Simple graph search. Simple patch finding, BFS, DFS, there's already enough kata to make it boring.

- Search for keywords to see if someone has done the idea before. Many topics has been already extensively covered. There are many kata related to Fibonacci numbers, factorials, fizz-buzz, and other common topics. Even some very advanced topics have many similar kata. For example, while Peano and Church numbers are definitely not easy, as the search results clearly show, they've been done many times already.

- Solve more kata. This way you will get better feeling of what is already there and what topics appear often in search results. Naturally, when you've already solved 10 Fibonacci kata, solving another one will make you very nauseous, making you naturally allergic to duplicates ;-)

Kata quality

Even the best idea won't save the kata if it's implemented poorly. Lucky for you, there's a set of quality guidelines which, when followed, will ensure that all pieces of your kata will be created properly. There's quite a lot of them and in the beginning they might seem a bit intimidating, so try to read through them and understand them, before you apply them to your kata. Remember that whenever you have any problems understanding something, you can always ask for help.

Learning from experience

There's no better teacher than experience, that's why it's never a bad idea to solve more kata, learn more, and then come back to creating your own. It can help one significantly in the following aspects:

- Getting more experienced will help you understand how hard your kata is, so that you can tune your kata to your desire easily.

- As you train more, you tend to know what the most efficient solution for a kata is. This is crucial to performance and golf kata: you don't want to make a performance kata when you can only write sub-par solutions! You'll get pwned hard by veterans ;-)

- Encountering kata issues and looking at comment sections will let you understand the common issues people will raise. Learn from history and don't make the same mistake again!

- Looking at solutions (and more importantly, solution comment sections) will give you an insight into what constitutes good practice.

- It also allows you to see how others write their tests. Writing good tests is hard, especially if your kata is also hard.

- By solving and reviewing beta kata you can learn a lot from mistakes of others and see what are the most common mistakes of kata authors, how reviewers react to them, and what are possible ways to resolve them.

Be aware though that there's many old kata which were created long time ago and do not hold to current standards. Bad quality of an existing kata is not an excuse for creating another bad one!

Setting up the kata

Kata are edited with the kata editor tool, described in the Kata Editor UI reference. To fully set up the kata you have to provide some basic information, as well as write some code in the language(s) of your choice.

Kata Properties

Name

The name is used to uniquely identify a kata. You can be creative with the name that you use. The best practice is to use a name that gives other users a good idea of what type of challenge they will be getting themselves into.

Discipline

The discipline is the category that the kata belongs to. You should pick the category that best describes what the kata is intended to focus on. As of now, there are five categories:

- Fundamentals - Focuses on the core language and API knowledge.

- Algorithms - Focuses on the logic required to complete the task.

- Bug Fixes - Focuses on taking existing code, determining the issue, and fixing it.

- Refactoring - Focuses on taking existing code and making it better.

- Puzzles

Estimated rank

Here you specify how difficult you think your kata is. This value is used as an initial estimate for the kata difficulty and will be refined while collecting rank votes from other users who solved it. Your perception of the difficulty of your kata might differ from what the community might think and estimate, so your kata may end up approved with a higher or lower rank.

Tags

Tags are used to classify your kata and make it easier to search for. Some tags are derived from the assigned discipline and added automatically, but you can add more.

Allow Contributors?

If you allow others to contribute to your kata, they will be able to make changes to it when it's a subject of the beta process. However, even when you do not allow for contributors, sufficiently privileged users will be able to edit your kata if it has some pending issues or requires fixing.

You can check the list of privileges to see who can modify your kata.

Description

The description field is used to provide instructions to the users who will be training on the kata. This field recognizes Github flavored markdown with a set of Codewars extensions. You can use the Preview tab to see how it will look like when presented to users.

The description of a kata is the first thing others see and forms the basis of users' first impressions. If the description is good, users will probably be encouraged to take the kata further. Otherwise, people won't hesitate to raise issues and downvote your kata.

Writing good descriptions is a difficult task, and you should refer to "Writing a Kata Description" guidelines to ensure that your description is of sufficient quality.

Code Snippets

To make your kata runnable, you need to write some code. Kata code is divided into a couple of snippets, each of them having a specific role, and being used in specific circumstances.

To keep the kata easy to maintain, every snippet is subject to quality guidelines, both general, and a set specific for each of them.

Complete Solution

You need to provide a solution to your own kata, to prove that it can be solved at all. The author's solution is run every time the kata is published, to verify the correctness of tests and the general kata setup.

Initial Solution

The initial solution is what users are provided with when they start training on your kata. How you set up your initial solution code will depend heavily on the discipline that you have selected. For bug and refactor disciplines you will end up needing to include an almost working or already fully working solution within this block. For fundamentals and algorithm disciplines you will likely only include skeleton code, such as an empty function/method or some other code that has gaps that need to be filled in. Sometimes you may just want to include some comments to help get the user started, but no actual code.

However, imagine the following scenario (assuming a statically typed language): you train on a kata that requires you to implement multiple functions, but the Initial Solution does not give you the relevant function signatures and hence fails to compile. You frantically read through the kata description and the sample test cases to figure out the function signatures you need to add: the name of each function, the number of arguments to each function, the type of each argument, the return type of the function ... After fumbling with the initial solution for a full 15 minutes, you finally get it to compile. Now you can actually focus on the task at hand. Not cool, right?

Unless the focus of your kata is debugging or your kata involves some deep C++ compile-time metaprogramming where 50% of the challenge itself is to make the code compile, you most certainly do not want the solver to waste their precious time fixing the initial solution just to get it to compile. The initial solution should provide the solver with a dummy implementation that "works" out of the box (possibly with runtime errors) such that they can start replacing the dummy implementations with their own code straight away. It is a kata issue if the initial solution fails to compile, especially if it introduces unnecessary overhead for the solver.

Note that similar principles apply to interpreted languages (e.g. JavaScript, Python, Ruby): the initial solution should not contain syntax errors and/or (top-level) reference errors which may prevent the solver from getting started with the task immediately.

Preloaded

The preloaded code block is an optional feature that you can use if you need it. The code from the preloaded snippet cannot be edited by the user, but it's available for all other snippets (solution and tests) to use. It's useful for when you want to load some code that mimics an API that your kata is based around. It's also useful if you want to define some code that needs to be used within the solution, but shouldn't be editable within the solution itself. For example, it can contain classes or constants which should be common for both solution and tests.

Working with preloaded code is sometimes tricky, and that's why a set of guidelines related to this particular snipped has been created.

Test Cases

The Test Cases editor is used to write submission tests: code that will validate the kata solution. Tests are not visible to the user, and the user solution needs to pass them for the kata to be considered complete. Every language on Codewars is set up to provide you with a testing framework that you can use to write test cases, organize them into groups, and assert on tested conditions. You can find out what testing framework you need to use by visiting the reference page of your language.

Tests are a very important aspect of every kata, and, after the description, are probably the second factor determining its quality. Bad tests attract negative feedback and are a very common cause of auto-retirement for beta kata. Good tests, on the other hand, are highly appreciated by users training on your kata. Writing good test suites is very difficult, often the most difficult part of creating a kata. It often requires more code than the actual solution. Make sure you follow quality guidelines for submission tests when writing them, as they will help you avoid many common pitfalls awaiting inexperienced authors.

The key thing about tests is that a test should perform two things:

- Accept all conforming solutions

- Reject all non-conforming solutions

Some people might think that only point 1 is necessary, but this is not true: tests that accept everything are pointless. Good tests will let all correct solutions -- and only correct solutions -- to pass.

For a normal kata, a good set of tests should cover all of these aspects:

- Test basic functionality

- Has full coverage (if that's impossible, at least have decent coverage)

- Cover edge cases thoroughly

- Randomized tests to probe user solution with random samples (and so that pattern-matching against the tests is impossible)

- Stress/performance/code characteristic tests if needed

The first three should be put into fixed tests. The fourth item should be put into random tests (see below). Ideally, the last item would be in isolation or covered by random tests. The last item is optional.

Random test cases are test cases that cannot be predicted. Most kata have them (except for the really old ones) and they are usually in addition to some static tests. Using both static and random test cases make it both easy for users to see what they are supposed to do, as well as make it impossible to write a solution that just pattern match the inputs (i.e. return hard-coded outputs depending on a fixed set of inputs). Random tests are also good at finding edge cases.

Remember: just like in real life, if we failed a test, we want to know:

- the input

- the expected and actual results

So unless revealing the expected result would spoil the kata, you should not hide them. Consult the documentation of the testing framework used by your language and pick the best method for your tests.

Example Test Cases

Example test cases are a small set of tests that the user can see and modify while working on their solution. These are some basic test cases that users will see when they load the kata. Sample tests are written in the same way as submission tests, using the testing framework set up for your language.

Except in circumstances where providing sample tests to the user would spoil the kata (such as Defuse the bombs), they are absolutely required as users can get an idea of how the solution is called and tested. You should include a few tests to get someone started, and the easiest way is just to copy over the fixed tests from the full test suite to serve as the sample tests. It is a kata issue if there are no sample tests unless strong justification can be provided against them for a particular kata.

Since sample tests can significantly impact the user experience of a kata, they have a dedicated set of sample tests authoring guidelines.

Before publishing

When you have finally written all the code, prettified the description, and verified the tests, you consider your kata good to go. But this is a very good moment to take a step back and hold back with publishing the kata, at least for a short while. While working on your kata you were focused on it so much, you probably missed some issues or possible improvements. If you rush publishing it, you risk others will find problems you missed, and your kata will be downvoted, or even insta-retired.

Train on your kata

A good first step is to train on your own kata. Getting in the shoes of a potential user is a nice way of checking what others will see and experience while training on your task. Although it's not possible to complete a kata being still in draft, it's still possible to train on it. Just open your kata in the trainer and try to solve it as any other user would do. This way, you can spot some problems with tests you may not have thought about before.

Verify quality guidelines

The next step would be to read through authoring guidelines once again, and use them as a checklist to verify that your kata conforms to the applicable ones. Remember that the guidelines were collected based on the community's experience with many bad quality kata published back in the days, so take them seriously and approach them with proper attention. If you do not understand some guideline or you are not sure whether your kata violates it, just ask more experienced users for advice.

Ask for a review of your draft

Drafts of kata cannot be found and searched for, but can be accessed by other users with direct links. You can share the link to your not yet published kata with others, and they will be able to read the description, train on the kata, and provide some feedback, before getting a chance to downvote it. Sharing a link to a draft is a very good way to get quick feedback about the most obvious problems.

After publishing

After you publish your kata, it becomes subject to beta evaluation. Power users immediately jump on it, knowing they will find problems, the kata discussion section will be flooded with issue reports marked with red labels, and the red, sad-faced button of the "Not Satisfied" vote will cause the satisfaction rating to drop to 20%. Unless there aren't any serious issues. It may be discouraging at first, especially for new authors, but when you think about it, it makes sense: after all, no one wants a bad kata to get out of beta, right? That's why it's important to make sure that when a kata is published, it's already in as good a shape as possible.

But still, no matter how hard you try, it's not possible to make everyone satisfied. Your kata may receive many satisfied votes, but even then, some users might not like it. Do not worry about this too much. Consider their remarks, and think a bit about them. Maybe they are right, and the kata needs some improvements? Listen to everyone, answer their questions, consider suggestions, and fix issues popping up. Also, do not rush things too much. If someone says something you are not sure about, just wait for another opinion. Users often do not agree with each other, so you can receive two mutually exclusive opinions. It can be difficult sometimes, but you just need to pass on one of them, or find some balance in between. Research shows [citation needed] that kata with authors actively maintaining them leave beta quite quickly, while some kata can be retired within minutes, or, even worse, stay in beta forever, if authors do not want to fix problems.

After your kata gets published and it gains a couple of solutions, it's very probable that someone will translate it to some other language for you. This is great, but do not get excited about this. It's recommended to hold back with approving new translations until the original version settles down, gets all isues resolved, and the kata matures a bit. When someone reports some design issue with your kata and it needs to be changed in some way, approved translations can make it difficult and they become additional maintenance effort. High maintenance cost is something you want to avoid at the early stage of a kata, when it's expected to change a lot.

After the kata collects enough positive feedback, it leaves the beta phase and becomes available for everyone to train on and earn their points. Now it will draw even more attention, and potentially thousands of users will submit their solutions, possibly finding new problems reporting new issues, and raising new suggestions. Your task, as an author, is to actively maintain the kata. This will encourage others to train on it more, provide translations to other languages, and enjoy it to its full extent.

Congratulations! Your first Codewars kata is a success!